Musk Is a Decade Late to Build a Super App

A deep dive on Musk's ambitions to turn Twitter into WeChat and why his top-down approach is antithetical to how Asian super apps were born

As you know by now, the “bird has been freed” (or not depending on your political leanings).

Last month, Musk finalized the Twitter deal and bought the company for $44 billion—making it the third-largest tech acquisition in history. But freeing the blue bird didn’t come easy or cheap for him.

At $54.3 per share, Musk forked out a 38% premium over its price on April 1 when he announced the 9% stake in Twitter and his buyout plans.

That is not bad for an indebted social network that has never found a path to sustainable profitability, is ridden with bots, and has been in decline in terms of its revenue and “heavy Tweeters.”

Not only that, Musk had to take on quite a fat chunk of debt to pull off this deal.

Before the acquisition, Twitter held $4.2 billion in long-term debt. And now that the deal has gone through, it will bear an extra $13 billion in debt from financing, which will be a massive burden.

In fact, it makes this takeover the largest leveraged tech buyout on record.

By Matt Levine’s calculations, the interest on that debt will range from 6% to 11% based on commitment letters from banks. That is roughly a billion in annual interest payments alone.

With Twitter’s most recently disclosed cash flows at $1.1 billion, Twitter will use most of its money to service its debt.

BUT that’s assuming Twitter will go about its old ways, which Musk isn’t keen on.

All political “free speech” rah-rah aside, Musk wants to retransform Twitter’s business model from the ground up. More specifically, he thinks he can turn Twitter into the West’s first super app.

Although little-known in the West, super apps are ubiquitous in the Far East. In short, they consolidate all digital services into one app—from messaging and streaming to ride-hailing and even banking.

Think ordering Uber, watching Netflix, shopping on Amazon, or taking out a loan straight from the Facebook UI.

China’s WeChat is the most notable example, which Musk took inspiration from for his “X” super app.

In his first address to Twitter employees back in June, he said:

“I think that there’s a real opportunity to create that. You basically live on WeChat in China because it’s so useful and so helpful to your daily life. And I think if we could achieve that, or even close to that with Twitter, it would be an immense success.”

Successfully building the WeChat of the West has implications that go beyond Twitter.

It could shake up the entire app ecosystem and eat into the duopoly of Apple and Google. It could usher in behavioral changes that can flip upside down how we transact or consume any digital services.

But the trillion-dollar question is… can Musk pull that off? Today we’ll try to answer that.

The rise of super apps

Before we begin this discussion, we have to get the definition of a “super app” straight.

While there are many ways to put it, the best generalization I can think of is an app that serves all your fundamental digital needs. As Tencent puts it, “It’s one app to rule them all.”

The world’s biggest app that’s come closest to this definition in its geography is WeChat. It’s one of the most widely used apps with over 1.2 billion users, most of whom are in China.

WeChat started in 2011 as a mere messaging app that was supposed to copycat WhatsApp. But over time, it’s evolved from messages into an indispensable, all-purpose hub for digital services.

You can use it to chat, shop, and pay both online and offline. In fact, its QR code-based payments are so ubiquitous in China that you can even use WeChat to pay at a street market.

Source: VCG

Its built-in “mini apps” can hail you a ride, stream media, book a doctor's appointment, and do all kinds of other things. And there are 3.5 million more such apps on WeChat, which makes it twice as big as Apple’s App Store.

You can think of it as an app version of iOS that has its own App Store yet is hardware-agnostic.

Here’s a great account of what that’s like from a Hong Kong-based Bloomberg columnist:

I live in Hong Kong and use WeChat routinely to connect with people on the mainland. On a typical evening before the pandemic, I messaged friends about where to meet for dinner, and they sent me the location of a diner. I hailed a taxi, listened to Taylor Swift, booked movie tickets to see Spider-Man, and then paid the taxi driver. At the diner, I scanned a QR code and perused the menu. We ordered, ate, drank, paid the bill, and hardly interacted with the waiter. On my way back, I booked a flight and hotel for my next trip and scrolled the latest news and celebrity gossip. All this time, I never left WeChat.

And here’s the kicker.

WeChat isn't included in any China app store lists because technically it isn't an app store. But if we consider it so, it would be the #2 most popular app store in China with nearly as many apps as “full-grown” app stores have.

Earlier this year, Tencent reported that WeChat’s daily active users for its mini apps grew to a record 450 million in 2021. That’s just 80 million short of Huawei, which is leading the pack.

WeChat has also been well integrated into federal services.

The Chinese government is piloting it as an electronic ID system, and using it for Covid vaccine passports, etc. (The government’s willingness to work with WeChat is rooted in its utilization as a surveillance tool, but more about that later.)

And so a whole new concept of the app was born from behind “the Great Firewall.”

But WeChat isn’t a one-hit-wonder. Many domain-specific apps across Southeast Asia are expanding their services both vertically and horizontally to become more all-purpose platforms.

Take Alipay, China’s biggest mobile payment platform, for example.

What began as the Chinese version of PayPal quickly turned into a one-stop-shop for payments—from wiring money to paying utility bills and traffic penalties—as well as many other services.

Gojek, probably the biggest super app outside of China, began as Indonesia’s “Uber”—a ride-hailing and food delivery service. It quickly became Indonesia's most downloaded app that processed hundreds of millions of transactions.

GoJek then used its payments infrastructure to tap the 64% of Indonesia’s population that was bankless at that time and become the leading mobile payments provider in the country—which offered Gojek a leg-up to expand into other verticals.

Today GoJek has over 20 services within the app, including Go-Mart (grocery delivery), Go-Clean (a housekeeping and cleaning service), and even Go-Massage.

Zuckerberg failed to build a super app

I bet reading the last section felt weirdly surreal.

That’s because we have grown up with standalone apps, each with full-fledged UXs tailored for their own purpose. And our digital infrastructure is designed to segregate them on an OS level, not within an app.

Also inspired by WeChat, Zuckerberg has been taking pains to change that since 2014.

Facebook has introduced many things on top of messaging. It has games as well as Twitch-like live streaming, podcasts— even a dating feature, which by all accounts has failed miserably against standalone apps like Tinder.

But all of them are auxiliary/niche. You couldn’t get by with Facebook the way you could with WeChat in China. You couldn’t hail a ride, or watch a TV show—never mind buying a bagel on the street.

In fact, Facebook piloted a native Uber integration in 2015 and planned to expand into other ride-hailing services. The promise was that you’d never have to leave Facebook to order a ride:

Fast forward seven years… this partnership is dead. Last I knew, folks are still popping up the Uber app.

Facebook’s latest big foray into the super app territory was the introduction of native payments and online stores. A few years ago, Facebook launched Shop, but has yet to brag anything about it.

I haven't found a mention of Facebook Shop’s success in terms of gross merchandise value that went through it. And they barely touched on commerce in the last three earnings calls.

Which means things aren’t looking up—at least not to a meaningful extent.

The only anecdotal data I found is from a couple of retailers sharing their experience of utilizing Shop as a showroom at best. From Digiday:

“Facebook and Instagram Shops are good platforms to represent your brand, almost like a calling card or a mood board,” said Carlos Jorge, director of e-commerce at Fivestory, which retails luxury brands such as Missoni and Oliver Peoples. “But as a conversion platform, not so much.”

That’s saying something considering that it was launched at exactly the perfect time—right during Covid. This is when Shopify nearly doubled its revenue and tripled its gross merchandise value.

Why has Facebook failed to natively integrate a single digital vertical outside of messaging and content?

Part of it may be Facebook’s fault (or impotence). Ryan Rodenbaugh of East Meets West accurately observed that, unlike WeChat, Facebook tried to branch out in-house rather than through acquisitions.

From “Aspiring Super App Series #1: WhatsApp + Facebook”:

One of the aspects that makes Super App harder in the West, that Tencent used to its advantage in China, is the ability to invest in and acquire meaningful ownership stakes in the companies that you will support as Tier 1 partners within your Super App.

Can you guess what’s in common about all of the companies powering [the featured services within WeChat]? In most cases, Tencent is one of the company’s largest shareholders.

Didi (Ride-Hailing) – Tencent owns ~20% of Didi.

JD.com (Specials) – Tencent owns ~17% of JD, a ~$100bn+ public company

Moguejie (Women’s Fashion) – Tencent owned 17.2% at the time of Mogu’s 2018 IPO

Zhuan Zhuan (Used Goods) – Tencent led a $200M round in 2017

Ke.com – (Housing) – Tencent led a $800M round in 2019

Pinduoduo (Buy Together) – Tencent owned 18.5% at the time of the IPO. Tencent first invested in PDD in February of 2017 and added them onto the WeChat Pay page in February 2018

But the other part of the reason isn't necessarily Facebook’s fault.

Why the West didn’t buy Zuckerberg’s super app

There are a few hypotheses about why Facebook—with all the money and momentum in the world—couldn’t knock off WeChat.

#1 Asian super apps built digital infrastructure, not aggregated it

By the time WeChat began consolidating services on its app and Facebook tried to copycat it, the West already had a well-established internet infrastructure built around standalone apps.

Each vertical had relatively large players with growing moats.

For streaming, there was then seemingly irreplaceable Netflix with over 75 million users. Uber was already six years old with tens of millions of active riders and over a million drivers on the road.

Back when WeChat integrated Didi into its app, the ride-hailing giant was just two years old and reportedly had 20 million users, max. For the size of its market, the company was minuscule.

For some perspective, Didi now has 550 million active users globally—five times as many as Uber.

So, coupled with the fact that Tencent was one of its largest shareholders, WeChat’s integration was a no-brainer entry-to-market strategy. And it worked wonders. Within a year of the integration, Didi doubled its active users.

In fact, the integration was so successful that some regions saw over half of Didi users ditching its standalone app for WeChat: “Some large cities like Wuhan (a population of ~11 million) are seeing 60% of DiDi users switch over to WeChat Pay,” Ryan wrote.

Apart from the exposure to WeChat’s users and a good UX, the providers of digital services found that mini apps were easier and cheaper to build than standalone apps on a mobile OS.

For that reason, some of them chose to build on WeChat only. From WeChat: A Not So Brief History:

In July 2014, Tech in Asia published an article foreshadowing the growing trend in China of entrepreneurs choosing to build their apps solely on WeChat and not bothering with iOS and Android applications. Though there are tradeoffs to not having your own app, one founder said, “With 400 million active WeChat users, getting access to them outweighs any cons.”

The bottom line is Didi to WeChat ≠ Uber to Facebook. WeChat branched out when China was playing catch-up with the West in the mobile-first internet. And it was early enough in the game to establish itself as an alternative “OS.”

In other words, building on WeChat was a necessity for many Chinese tech companies rather than a nice-to-have.

#2 WeChat pioneered mobile payments in China

But at the very core of WeChat’s success was its early entry into mobile payments.

In 2013, WeChat introduced WeChat Pay and became the first social app that integrated payments. Back then, it had one predominant feature: the ability to send a fixed or randomized amount of money to your contacts.

These money transfers were called “Red Packets,” drawing from a century-old Chinese tradition of handing out red envelopes with money on special occasions.

Technically, a Red Packet was a primitive money transfer. But WeChat framed and gamified it in a way that contagiously caught on with the Chinese. From Eveline Chao, ex-Beijunger journalist (emphasis mine):

Mike said whenever people weren’t checking their messages enough, the producer would send a red envelope to the group, and everyone would go crazy. To me it sounded bizarre, the equivalent of your boss tossing a fistful of change at your cubicle. The producer would also send red envelopes as a reward to the cast and crew for their hard work.

A few days later, a Red Packet icon appeared in a chat stream I had going with friends back in China. I tapped on it, and a full-screen message announced that I had received 0.03 yuan—a fraction of a cent. It also said my friend Julian had opened one too, that we had taken 11 seconds to do so, and that I had opened mine first. I felt ridiculously excited, like I’d won way more than part of a penny. That was when I started to understand the competitive, gambling-like thrill of Red Packets.

WeChat’s red packets were so successful that Alibaba’s Jack Ma called it a “Pearl Harbor Attack” on Alipay.

This is how WeChat Pay took advantage of its social clout to push payments for its hundreds of millions of users. Anu Hariharan of Y Combinator put it nicely:

The growth of WeChat Pay was initially driven by close tight knit social circles - friends and family sending money to each other and they were willing to connect their bank accounts to do the same. This important move was necessary to build trust among users and to inculcate the user behavior to drive mobile payments before extending this feature to more shallow circles like paying merchants, online and offline stores.

But part of the reason WeChat Pay caught on so quickly wasn’t just its ingenuity with Red Packets. It was the fact that China was still a cash-dominated economy—never mind mobile payments.

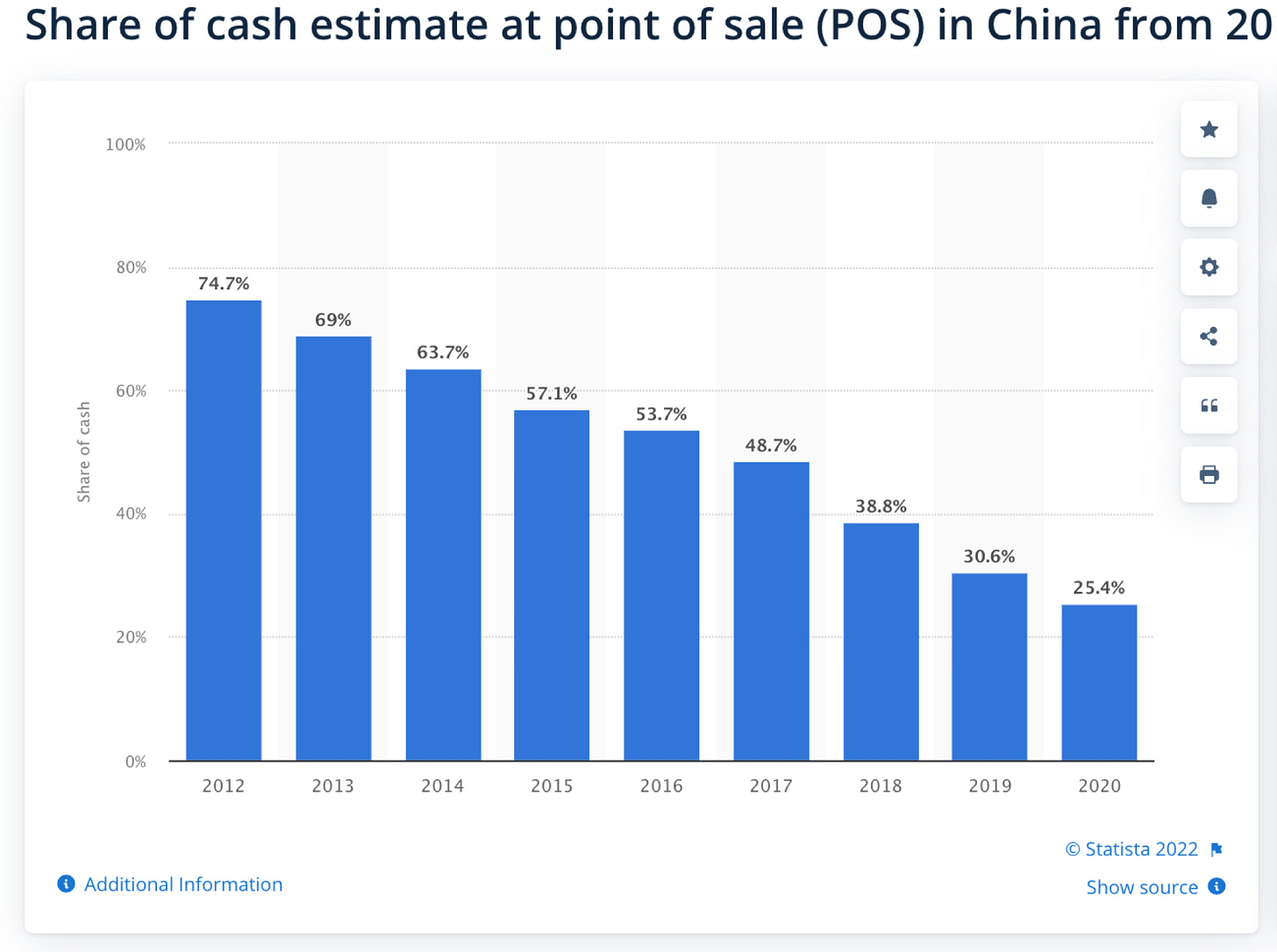

In fact, back in 2014, when WeChat began integrating its payments into third-party apps, 64% of all offline transactions in China were cash:

And of that one-third of digital payments, only one in ten was mobile:

That’s where the famous QR code came into the picture.

As one of its pioneers, WeChat introduced QR code-based payments that let any offline retailer—from grocers down to measly street vendors—accept mobile payments without the need of expensive POS.

The POS became a mere slip of paper with a QE code stamped on it:

QR payments blew up so quickly that in just five years they replaced both cash and credit cards in China. They are the reason China skipped through the digital banking phase and jumped from cash straight to mobile payments.

Even the Chinese homeless beg for “digital change.”

In the end, WeChat became a gateway into China’s cash-dominated population. And its payment infrastructure was the second big draw for other services to build on WeChat as opposed to starting from scratch.

Which ties back to the first point that WeChat became a super app as an unintended consequence of building China’s digital infrastructure, not by aggregating already full-fledged services.

#3 The government's support in exchange for a surveillance pass

The last but not least leg-up WeChat had was immense support from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Tencent is a state-owned company that has received generous subsidies from the government. The CCP also built the “Great Firewall” that effectively ousted its competition in standalone apps—including Messenger, WhatsApp, Uber, Netflix, and others.

In return, Tencent gave in to the CCP’s censorship and surveillance mandates. As MIT Technology Review exposed in 2019, the CCP forced Tencent to real-time censor and surveil people even in private conversations.

It was a win-win for the CCP and Tencent.

For Tencent, the CCP culled the competition and turned a blind eye to WeChat’s monopolistic nature. And for Xi Jinping, letting Tencent build the “ultimate” app fit into his technocratic vision because it gave him the ultimate enforcement tool.

Of course, Chinese tech billionaires didn’t come into bed with him voluntarily. And if they attempted to resist it, they would “mysteriously” disappear from the spotlight. (Remember Jack Ma’s going offline for three months?)

But whether they liked it or not, the Xi authoritarian shtick was a major factor behind the success of their super apps.

Which brings us to Musk’s Twitter acquisition with the hope of turning it into WeChat…

With all this in mind—the fact that the CCP not only allowed but encouraged super app monopolies for its own benefit, and that Tencent, in fact, pioneered rather than aggregated most services….

Can Musk knock off WeChat?

Last week, Musk held the first all-hands meeting with Twitter employees. He reiterated his super app ambitions and answered questions, which can give us a bit of a sneak peek into his plan.

From license filings and emphasis at the meeting, it looks as if payments will take the highest priority.

WeChat showed that building a super app is a matter of controlling people’s wallets. And if Musk wants to replicate them, he has to prime people to transact through Twitter, which he’ll try to do:

“I think there’s this transformative opportunity in payments. And payments really are just the exchange of information. From an information standpoint, not a huge difference between, say, just sending a direct message and sending a payment. They are basically the same thing. In principle, you can use a direct messaging stack for payments. And so that’s definitely a direction we’re going to go in, enabling people on Twitter to be able to send money anywhere in the world instantly and in real time. We just want to make it as useful as possible.”

The end goal is to turn Twitter into a competitive full-fledged neobank. That includes offering interest-bearing money market accounts and even loans, which he hinted at in a recent Twitter Spaces:

"Then the next step would be to offer an extremely compelling money market account to get extremely high-yield on your balance. And then add debit cards, checks," he said.

During that broadcast, a Twitter employee noted that Musk's payment vision resembled a bank and asked if Musk planned to introduce loans. “Well, if you want to provide a comprehensive service to people, then you can’t be missing key elements,” he responded

Again, this cross of a social app and bank isn’t novel. That’s exactly what WeChat successfully integrated years ago.

In 2014, WeChat Pay launched China's first neobank, WeBank which was seamlessly integrated into WeChat. Today it’s the largest private bank in China with 350 million customers and $212 billion in assets under management…

… which are growing 50%+ YoY.

(Note that WeChat was China’s first digital-only bank, so part of WeChat’s success was having a first-mover advantage. But more about that later…)

Musk also alluded to branching out into long-form video and introducing TikTok-like recommendation algorithms.

We’re not trying to put YouTube out of business, but I’m just saying, do we really need to give YouTube a whole bunch of free traffic? Maybe not. So at least give creators the option if they would like to put their video on Twitter and earn the same amount as they would, or maybe slightly more, on YouTube or TikTok or whatever the case may be. I was actually flipping through the Twitter video where, once you go into kind of a full-screen video mode, you can just start flipping through videos. It’s actually not bad. I was like, “Okay, well, it’s pretty good.” I think building on that makes a ton of sense.

But typical of hardcore Musk, it seems that the plan is to have no plan. Throw a bunch of spaghetti at the wall and see what sticks. And do that in a “maniacal sense of urgency.”

He even explicitly gave Twitter users a heads up about a lot of “dumb stuff” that will come out as a by-product of this trial and error:

Which puts Twitter in a bit of a pickle.

Being a cash-burning private company, Twitter can’t afford trial and error for long. By Musk’s calculation, Twitter is now losing $4 million a day, which amounts to nearly $1.5 billion a year. If Twitter wants to survive this recession as well as advertiser boycotts, Musk thinks that half of Twitter’s revenue has to come from subscriptions. That means Musk doesn’t just have to jack up revenues, he has to flip its business model upside down, make it profitable, and pull that in a relatively short time.

Musk doesn’t have the luxury of being a first-mover. Each vertical Twitter is coming after, from video to payments, has well-established players. Not only do these brands have multi-faceted moats, they’ve also played a formative role in shaping digital culture in the West. To transform consumer behavior Musk will have to offer something extraordinarily compelling or buy out its competitors, which Twitter doesn’t have nearly enough money to do. As Ben Thompson said of his ambition to turn Twitter into a bank: “Once a job is done – and credit cards do their jobs very well – it takes a 10x improvement to get users to switch…”

Unlike CCP-controlled WeChat, Twitter and Musk aren’t subsidized by the government, nor do they have political immunity. Quite the opposite, his agenda is a direct attack on the establishment (i.e. Democrats), and for better or worse, they’ll find a way to come back at him. In fact, Senator Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) already called on the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) to probe Twitter on national security grounds. Even if he’s successful in building a super app to some extent, how long before the DOJ will start throwing antitrust lawsuits at him?

And last, he can’t use his eccentric charm to attract dumb capital anymore—which worked wonders for Tesla—because Twitter is out of reach for 99.9% of investors. (Unless his memes will enchant more Saudi royals with deep pockets.)

Top-down innovation

In The Evolution of Everything, Matt Ridley argues that innovation isn’t a product of genius but evolution. It’s a spontaneous order that fills a need driven by collective changes in culture, technology, and the economy.

Or, as he argues, if it weren’t for Steve Jobs, somebody else would have figured out that people need a computer with a good UX.

That was WeChat— a messaging service that incrementally evolved into a super app by solving pain points China was long ripe for. With Twitter, it seems that Musk is trying to force that from the top down.

Can he turn Twitter into WeChat?

I doubt it—if for no other reason than regulators.

But that doesn’t mean he can’t iterate Twitter to something of value in the end. Who knows, he may test out something crazy—as he often does— and stumble on his own “Red Packets.”

If Musk taught us anything, it’s that you should never underestimate his ability to beat the odds. I’m skeptical, but, frankly, I have been skeptical about pretty much everything he has undertaken.

And all too often he’s proved me wrong.